Andre was enjoying the carefree life of a 12-year-old with his friends, riding his bike and playing sports, like all kids that age. Schoolwork wasn't hard for him, and his grades showed that.

Then, the headaches began.

He lost vision in one eye, symptoms that drove his family to seek medical care at a Moscow hospital in 1994. The days became a blur as doctors performed radical surgery to remove as much of the mass — later identified as a grade IV glioma, a fatal form of brain cancer — as could safely be cut from the boy's brain.

Radiation to the brain followed surgery, then chemotherapy with tamoxifen, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, carboplatin, etoposide, and cisplatin. Despite the aggressive chemotherapy, Andre's tumor continued to grow, and his functional and neurologic status deteriorated until he became unable to speak, required a wheelchair, and started to have seizures.

There was no time or energy for any normal life for Andre, and the cadence of the family's once peaceful life shifted to one consumed with medical appointments, tests, doctors, and hospitals. But, Andre never lost the support or hope of his family.

By now, the boy was in Israel, and it was April 1996 when Dr. Laszlo Csatary, a cancer specialist, approached him with an alternative treatment option: a virus. If doctors infected him with Newcastle disease virus, that infection might, maybe, kill his cancer. The patient and his family felt he had already exhausted all options available in conventional therapy and consented to the treatment.

Early in his medical career, Csatary had heard the story of a Hungarian farmer whose aggressive metastatic colon cancer regressed following an outbreak of Newcastle disease virus on his farm. The story would shape his life's mission to treat people with aggressive cancer, like Andre.

As a young doctor in 1968, practicing in the Alexandria, VA, with admitting privileges at the nearby Jefferson Memorial Hospital, Csatary grew frustrated with the lack of treatment options for an elderly patient with advanced-stage cervical cancer. He sought permission to treat her with Newcastle disease virus. Unfortunately, she died a year later. But not from cancer. She died of heart disease, and her autopsy found her free of cancer.

Fate, luck, or other forces worked to cross the paths of desperate and brave folks like Andre, with the paths of forward-thinking doctors like Csatary. For Andre and Csatary, it was a pivotal time that neither would forget.

From Deadly Poultry Virus to Cancer Killer

Newcastle disease virus is a virus that infects birds and causes serious respiratory and gastrointestinal tract infections in poultry. One of the first outbreaks of the virus occurred and in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England, giving the virus its name.

Birds infected with Newcastle disease virus cough, sneeze, experience spasms, and paralysis, then die. The infection is highly contagious and spreads through a flock quickly.

Virulent strains of the virus are endemic in poultry in most of Asia, Africa, and some countries of North and South America. Different types of vaccines against Newcastle disease virus have been developed and provide some immunity, but import restrictions and eradication efforts aimed at promptly destroying infected poultry have kept it out of the US and Canada. Authorities in California have killed more than 1.4 million chickens due to infection with the virus.

A chicken infected with Newcastle virus.

The idea of using an infection with bacteria or viruses to treat cancer started with an observation in the mid-1800s that tumors regressed in some people after they had an infection. In fact, in 1891, William Coley succeeded in decreasing the size of a cancerous bone tumor by injecting the patient's tumor with streptococcal bacteria.

Newcastle disease virus rose as a suitable anti-cancer candidate because it was known to be an oncolytic virus — a virus that specifically destroys cancer cells by breaking them apart, but more importantly, doesn't destroy healthy human cells or cause disease in humans. Researchers hoped that if administered correctly, the virus might attack and kill cancer cells, without causing a deadly illness to the infected person.

The bird infection is safe for humans because of a phenomenon called viral tropism. Viruses are specifically geared to attack cells of a certain species, so if another species is too genetically different, it won't be able to infect it.

"A simple rule of thumb is that the more closely donor and recipient host species are related, the easier it will be for any virus to jump between them and establish a productive infection," Tibor Bakacs, MD, a colleague of the late Csatary, explained. "Key components of the virus-host interaction in birds and mammals diverged along with their hosts during more than 200 million years such that 13 mutations may be required for avian influenza viruses to establish productive infections in humans."

"Consistent with this, while Newcastle disease virus causes a potentially fatal, noncancerous disease (Newcastle disease) in birds, it causes only minor illness in humans (flu like symptoms)," he said. "In other words, Newcastle disease virus replication in normal human cells is very limited."

The first findings on the use of Newcastle disease virus (and other viruses, including Sendai, Sindbis, Influenza A and B, and Semliki Forest Virus) to treat a patient with leukemia were reported by two researchers out of the Western Reserve University School of Medicine, in 1964. Unfortunately, the patient died, but temporary remissions followed each viral injection.

Researchers didn't do much else with Newcastle until the 1980s. A study by researchers at the Emory University School of Medicine showed positive effects of treatment with a Newcastle disease virus oncolysate — an extract made from cancer cells infected and killed by the virus. Eighty-three people with malignant melanoma — an often fatal type of skin cancer — were given the lysate after surgery, and ten years later, more than 60% of them were alive and free of recurrent disease. According to the paper, the survival rate at ten years is usually about 33% in these types of patients.

In 1993, a Hungarian research team led by Csatary tested the approach, using a weakened form of Newcastle disease virus, a strain called MTH-68/H. They also applied the virus in a new way. Because the patients in the study had cancer that had metastasized to their lungs, they delivered the virus by inhalation where it could directly target the growths. Study participants in their clinical trial were given either a placebo or virus by inhalation twice weekly for six months. After two years, 21% of the participants who received the virus were still alive. None of the patients who received placebo were alive.

But would it work for Andre?

The Magic of Newcastle Disease Virus

Over the next two and a half years, Andre received the virus intravenously daily — starting at one vial, then two, then three, then four a day as the Newcastle disease virus worked to destroy his cancer.

Several characteristics of Newcastle disease virus made it a very good candidate as a cancer therapy. It doesn't cause disease, has very few side effects in humans, and there is no pre-existing immunity to it — meaning our body's defenses will not react to the virus as soon as they see it, allowing time for the virus to work on cancer cells.

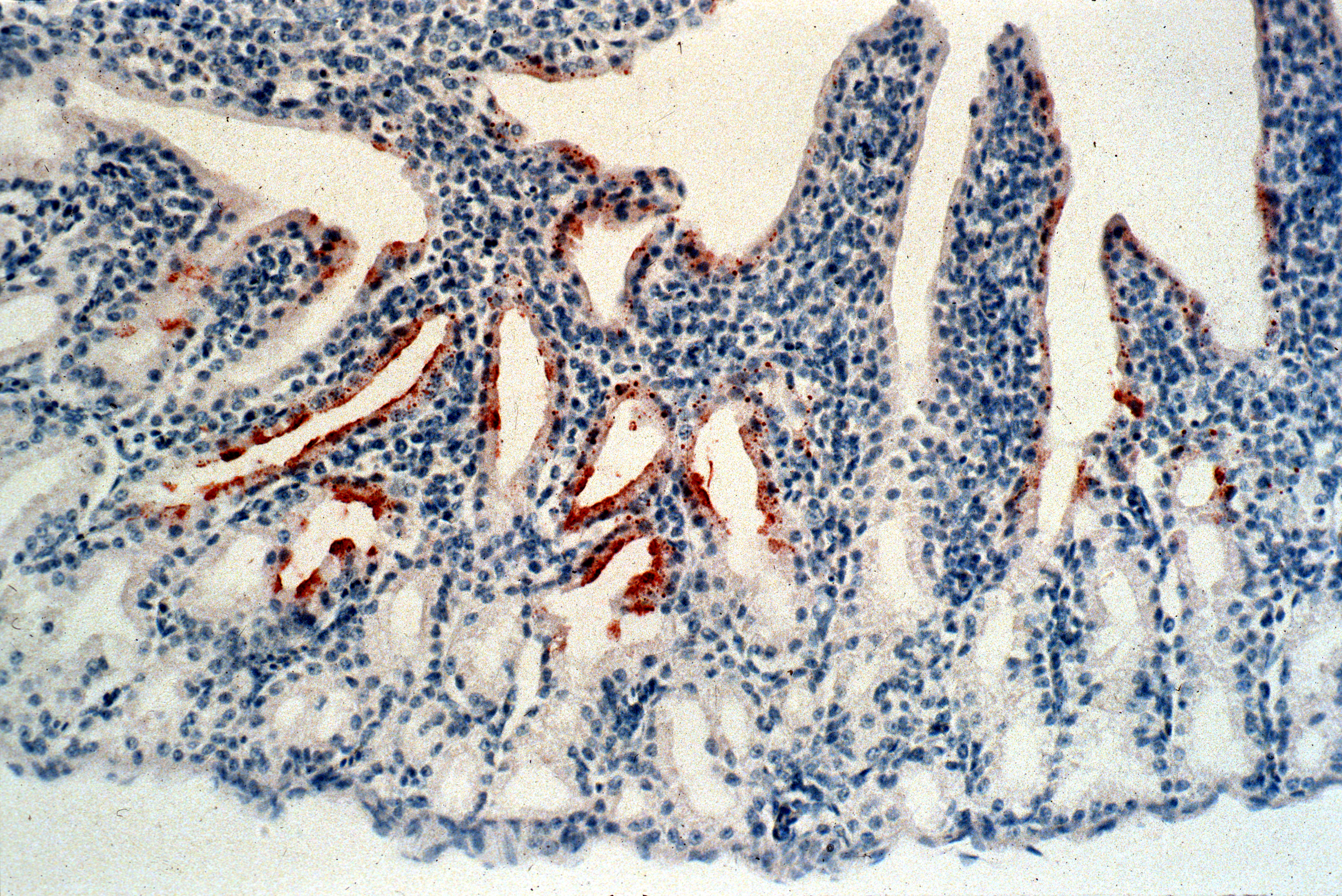

Newcastle disease virus in the conjunctiva of a chicken. The virus is indicated by the brown stain.

The virus specifically binds to human cells, enabling it to enter them. But the virus doesn't replicate in healthy cells. When infected, normal human cells rapidly produce antiviral proteins to kill the virus before it takes over the cell.

Cancer cells lack the organized internal structure of healthy cells and therefore, these defense functions don't exist. They're also defective in a programmed cell death pathway that lets healthy cells commit suicide when they're infected, injured, or mutated, and without it, the cancer cells just keep living even though their regular systems are shut off. That makes them excellent at creating productive viral infection and replication, according to Bakacs.

Capitalizing on this defect was what Csatary hoped to do with Andre.

Laboratory experiments and animal models have shown that Newcastle virus could infect, but not kill, healthy cells. It could kill a broad range of cancer cells including colorectal, stomach, pancreatic, bladder, breast, ovarian, renal, lung, larynx, and cervical carcinomas, glioblastoma, melanoma, phaeochromocytoma, lymphomas, fibrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, neuroblastoma, and Wilms tumor of the kidney.

What Opponents Say

Before the Food & Drug Administration approves a drug or therapy, it must pass rigorous testing. To understand the root of most criticism of the use of Newcastle disease virus to treat human cancer, we need to understand the different types of clinical trials. Human clinical trials are performed in at least three, and often four, phases, with increasingly large groups and longer time frames.

- Phase I: Enrolls 20 to 100 healthy volunteers or people with the disease or condition. Length of study: Several months. Researchers assess the safety and dosage of the treatment.

- Phase II: Enrolls up to several hundred people with the disease/condition. Length of Study: Several months to two years. Researchers analyze the treatment's ability to produce a desired or intended result and its side effects.

- Phase III: Enrolls 300 to 3,000 volunteers who have the disease or condition. Length of Study: one to four years. Researchers are looking for the same assessments as Phase 2.

- Phase IV: Enrolls several thousand volunteers who have the disease/condition. Assesses safety and ability to produce a desired or intended result.

Studies using Newcastle virus have been performed using different forms of the virus, administered by different routes, with variable results. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) list the following clinical trials of strains of Newcastle.

Clinical trials and case studies of Newcastle Disease Virus

In addition to these studies, two other phase II trials of NDV oncolysate were done in Germany. One of the studies showed that people in the trial had longer disease-free survival. A criticism of this study and earlier ones done in the US was that patients' survival time was compared to published information, and not to other patients in the study that researchers treated with another therapy or surgery alone.

The main criticisms of the clinical trials have been that they don't have adequate numbers of participants from which to make meaningful statistical conclusions, the participants were not randomized — meaning they were not randomly assigned to get either the viral treatment or some other treatment for comparison — and some patients continued to receive other therapies. In addition, one patient treated with the Newcastle strain PV701 for kidney cancer that had spread to the lungs died from what an autopsy showed was inflammation in her lungs due to an immune response to the treatment.

The National Cancer Institute's (NCI)'s primary concern about the use of Newcastle disease virus is that repeated injections may cause a person's immune system to form antibodies against the virus. The antibodies could attack the virus and prevent it from infecting and killing cancer cells. We also know that this immune response has also killed at least one patient.

However, NCI also had this to say about the use of Newcastle disease virus as a treatment for cancer:

"In view of the evidence accumulated to date, no conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of using Newcastle disease virus in the treatment of cancer. Most reported clinical studies have involved few patients, and historical control subjects rather than actual control groups have often been used for outcome comparisons. Poor descriptions of study design and incomplete reporting of clinical data have hindered evaluation of many of the reported findings. However, while most studies are small and lack adequate controls, the number of studies suggesting a potential clinical value warrants further attention."

Despite criticism, there is no denying the long-term positive response some patients have experienced. Those responses are what has kept some scientists from doggedly pursuing its use as cancer therapy.

How Human Cancers Respond to Newcastle Disease Virus

Some scientists have discounted Newcastle disease virus's successes as anecdotal, but others have tried to understand how it works to create a scientifically verifiable and reliably effective therapy.

Different modes of delivering the virus produce different immune responses in the body. When doctors administer the virus intravenously, the way Csatary did with Andre, a high or repeated dose is needed because the liver and spleen rapidly clear the virus is from the circulation.

The virus needs to infect the cancer cells, replicate, kill the cells, and move on to the next one to effectively do its job of destroying the tumor. During the time it takes for this process to occur, the immune system has time to ramp up and may respond by killing the virus.

Researchers have also seen that if the virus is injected directly into a solid tumor, the immune system sees the viral presence as a kind of "danger signal" and immune cells are attracted to the tumor. White blood cells are activated to recognize and kill cancer tumor cells. They then move throughout the body to infiltrate and destroy other tumors even if they were not injected with the virus, causing more a comprehensive response to the tumor.

Dr. Dmitriy Zamarin, a medical oncologist from Sloan Kettering Cancer Center wrote in his 2015 paper that the anti-virus immune response could be decreased either by genetic engineering of the virus or by use of medication to dampen the body's immune response to the virus.

"Since a major mechanism of action of Newcastle disease virus appears to be its ability to stimulate anti-tumor immune response," Zamarin said, "we have primarily focused our efforts on combinations of Newcastle disease virus with immunomodulatory agents and on engineering the viruses that could modify the tumor microenvironment to stimulate an even stronger anti-tumor immunity."

Approaches like Zamarin's may provide a foundation for the development of therapeutics that bring Newcastle disease viral therapy into the company of other current anti-cancer biologic and immunologic agents. They also may be a way to work around some of the opposition to injecting live viruses into humans.

The Future Is Now

Csatary died in 2012 without being properly credited for his work in many articles published on viral therapy, Dr. Ralph Moss said in Csatary's eulogy.

He swept the discrediting of Csatary's work aside by saying, "objective evaluation of the medical record leads to the conclusion that Laszlo Csatary made enormous contributions, by employing, clinically testing and publicizing the use of oncolytic viruses in cancer as well as other diseases."

Laszlo Csatary with Bakacs' son in Alexandria, VA.

Bakacs told Invisiverse that glioblastoma patients are still not cured by the treatments available at the moment — the estimated survival is 612.5 days after diagnosis — and says that Csatary's contributions and achievements in glioblastoma treatment belong alongside the likes of Nobel laureates. He speaks with humble thanks for his 15-year professional and personal association with Csatary.

Andre is living proof of that enormous contribution.

Andre continued to receive the Newcastle disease virus until 2002. While we can't say definitively that the Newcastle virus eradicated the glioblastoma, he survived the cancer, and the treatment, and remains well with no evidence of tumor, a miracle of sorts, given his seemingly hopeless situation. A year ago Bakacs met Andre in Jerusalem to personally connect with this patient who was so special to Csatary.

Now a young man of 34, he works as a secretary in an office in Jerusalem and is taking courses at the university. "Currently my condition [is] stable and MRI which I do once a year shows the same picture for years," Andre told us. "There are residual effects, right hemiparesis (limited movement of my right leg and arm) — that came after chemotherapy, prior to the virus treatment."

He hasn't followed the research on Newcastle virus but knows it's not in production anymore and the opportunity missed to save the lives of others saddens him. He doesn't wax poetic with sentimentality as he directly credits Csatary with saving his life. But, his undying respect and gratitude are evident in those few words.

As Andre mentioned, no companies are producing Newcastle virus as a cancer therapy, and there are no clinical trials underway.

Two prominent cancer virus researchers, Bakacs included, offered some insight into the situation. The bottom line they say — the profit line — drives the decisions of pharmaceutical companies to invest in research for any given disease or product. Bakacs said the failure of Newcastle disease virus therapy acceptance could be because a business model supporting such efforts is still missing, citing the difficulty in profiting from a natural product. Unless this virus could be modified to be patentable and unique in some way, its worth to a drug company is just not high enough.

Zamarin has more hope that we can overcome at least some of the developmental and potential profit obstacles.

"The virus strain was a potential bird pathogen, which likely made it difficult to develop further in the US," Zamarin said. "The research since then has been focused on using genetically-modified Newcastle disease viruses that are not pathogenic in birds."

"Despite being one of the oldest oncolytic agents, the understanding of the properties of Newcastle disease virus underlying its therapeutic efficacy is still in its infancy," said Zamarin. "There has been significant success over the past few years. Astra Zeneca has engineered Newcastle disease virus in its research portfolio, and we are waiting for the trials to hopefully commence within a year or so."

One encouraging development has been the Federal Drug Administration's 2015 approval of the first oncolytic virus, a modified herpes simplex virus-1, for treating melanoma.

In the meantime, "why should neuroblastoma patients have to wait for matching tumor features with 131 different drugs that might help treat diseases for which they weren't designed when Newcastle disease virus has already proved to be a powerful weapon against the most malignant neuroectodermal tumor, glioblastoma?" wrote Bakacs, Schirrmacher, and Moss.

Some patients aren't waiting. They are doing what many of us might do in a similar situation. Motivated by a lack of options and will to fight to survive, they search for alternative treatments. Some of them find it at a clinic in Germany.

Newcastle disease virus therapy is a treatment option offered by Robert Gorter at the Medical Center in Cologne, but that's the only clinic Zamarin's and our searches have found.

Cancer patients know of the clinic, though, and have read Gorter's book and talk about their hopes and experiences at his clinic on online forums like Inspire, an online community dedicated to members "sharing and learning about their medical conditions, treatment, and support." Patients also talk with one another about whether seeking treatment with Newcastle Disease Virus at his clinic is a good idea.

How far would you go to try to cure or even slow down your cancer? Would you risk trying a novel treatment that just might save your life?

Thanks to the dogged work of researchers willing to confront tightly-held biases in favor of chemotherapy and against viral therapy, and brave patients whose faith has transcended their desperation, we have 50 years of progress and successes on which to build future Newcastle disease virus therapies.

"We believe that in the future, when viral therapy is more widely accepted, Csatary will be widely acknowledged recognized as a true pioneer of this most promising branch of medical science," Moss wrote in his eulogy of Csatary.

Andre told me he never considered giving up and acquiescing to a fateful death. It just wasn't an option. In his words, "it might be the simplest way, but it's the wrong way."

Because he's not a doctor, he stops short of recommending the treatment, but what he does recommend is to be open to every opportunity and to open-minded, compassionate doctors like Csatary — and never, ever give up hope.

- Follow Invisiverse on Facebook and Twitter

- Follow WonderHowTo on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Google+

Cover image via Destroyer of furries/Wikimedia

Comments

No Comments Exist

Be the first, drop a comment!