To much of the United States, Zika seems like a tropical disease that causes horrible problems in other countries but is nothing to be worried about stateside. It may make you rethink your beach vacation abroad, but not much more than that. However, if you live in Florida or Texas, the possibility of getting a Zika infection where you live is real — and local outbreaks are more and more a possibility.

Infection with the Zika virus can run the gamut from mild to devastating. Most infected people don't have any symptoms, but it can cause Guillain–Barré syndrome — a disorder that affects the immune system and damages nerves.

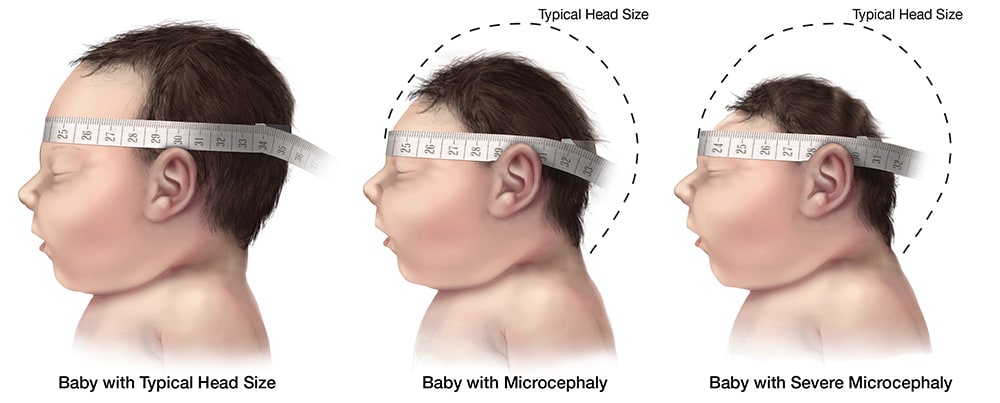

Additionally, if a pregnant woman gets the Zika virus, her baby may be born with a severely small head, called microcephaly, and other brain and medical problems. If the Zika infection is acquired in the first trimester of pregnancy, the chances the baby will be born with microcephaly range from 1 to 13 percent.

To get at the root of Zika infections in the US, it's important to distinguish between people in the States who have been infected with the Zika virus and people who have been infected with the Zika virus in the US. In the first case, those people were generally infected while traveling outside the US.

While there have only been 224 cases of the virus infecting people on US soil so far (not counting US territories) by local mosquito-borne transmission, they have been confined to Florida and Texas. An epidemic in those states could have wide-ranging health and financial implications. And increasing cases are more likely than we think due to shifting mosquito habitats.

But there's some good news. A research paper published January 3 in the Journal of Medical Entomology by Max J. Moreno-Madriñán of the Fairbanks School of Public Health at IUPUI, along with independent research entomologist Michael Turell, retired from the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, suggests that chances for a widespread epidemic in the US are small.

Still, a real threat of Zika infections remains in some southern US states as more Zika-carrying mosquitoes such as Aedes aegypti move north as the climate warms.

The Zika-Carrying Mosquito

To understand why outbreaks might happen, it's important to understand how the Zika virus gets transmitted to humans and the role certain types of mosquitoes play in transmitting the virus. The key to infection control is knowing which mosquitoes present the most risk, then crafting a bite prevention strategy.

Zika virus is spread through mosquito bites. Blood feeding on a human or other mammal is a critical step in the lifecycle of a female mosquito. If the mosquito carries the Zika virus, it can be injected into the human when bitten.

Given the complex nature of viruses, Zika is usually only able to infect the Aedes genus of mosquito, specifically the Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus species. These are the same mosquitoes that spread dengue and chikungunya viruses, two viruses that infect and sicken hundreds of millions of people around the world every year.

A. aegypti mosquitoes primarily bite humans, whereas A. albopictus feed on both animals and humans. Both species are already in California and other warm southern states. The fear is that warming trends will allow the mosquitoes to move into more states or to come and survive in greater numbers in those where they already live.

Usually, these mosquitoes are active during the day — from approximately two hours after sunrise to several hours before sunset, but they can also bite at night. People who use mosquito bite protection only in the evening will be at risk for bites from this mosquito during the day.

Both species breed nearclean water. The female mosquitoes like to lay eggs in small containers where water collects, such as discarded tires, flower pots, old cans, and clogged rain gutters. Standing water is a major contributor to mosquito populations — one easy way to reduce them is to drain these swampy water holes.

Where Is Zika in the US Today?

As of May 31, 2017, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed that Zika cases have happened in every state except Alaska since 2015, though the majority of these are infections brought home from abroad — acquired by travelers outside the US.

Laboratory-confirmed symptomatic Zika virus disease cases in the US during 2016.

But, make no mistake — the A. aegypti and A. albopictus mosquitoes are in the United States. They can survive year-round in tropical and subtropical climates, and A. albopictuscan even survive harsher temperatures than A. aegypti, but neither lives through the winter in the egg stage in colder climates. Areas where the eggs can survive the winter, like Florida and Texas, are the same areas in which A. aegypti and A. albopictus has been reported to cause infections.

The only cases of Zika acquired within the US so far, starting from 2015, were 6 cases in Texas and 218 in Florida.

Why Is the Risk of a Zika Epidemic Low in the US, but High in Some States?

The A. aegypti population in the US is lower than it might have been, had the mosquito not also been named the culprit in the spread of another disease.

In 1901, experiments conducted in Cuba identified A. aegypti as the mosquito responsible for spreading yellow fever. Efforts to reduce the mosquito in Cuba slowed the return of the mosquito into the US.

In a positive twist of fate — or a real scientific outcome — the decrease in A. aegypti in our geographically close neighbor has helped keep high numbers of the mosquito from making its way to the US and has helped keep our country-wide Zika rates low. Unfortunately, the tide seems to be turning now.

The new research study by Moreno-Madriñán and Turell in the Journal of Medical Entomology explained that the southern states are at risk for Zika infections — and possibly for more infections than we've seen so far. This new Zika research suggested that increasing globalization, urbanization, and travel as factors, combined with global warming and weather fluctuations due to El Niño, are likely to increase Zika infections in the southern US.

Moreno-Madriñán and Turell wrote in the paper that there are several reasons that the US as a whole will not likely see an epidemic the size that Brazil saw, where there were an estimated 440,000–1,300,000 cases in 2015 and 4,783 suspected cases of microcephaly.

Zika virus.

First, the routine and common use of window screens and air conditioning in the US means fewer mosquitoes get inside our homes. Second, widespread indoor plumbing in the US means less standing water outside, so less of a chance that mosquito larvae are brought indoors with water buckets.

The Future of Zika in the US

There's still one big worry about Zika's ability to spread in the United States: The common mosquito.

According to research presented back in May 2016 at the University of California, Davis, laboratory tests have shown that Culex spp., aka common mosquitoes, are also capable of harboring the Zika virus.

That's a dangerous proposition, since Culex quinquefasciatus, the southern house mosquito, is much more abundant than A. aegypti and lives throughout the southern United States. Scientists are catching and testing wild Culex spp. mosquitoes to see if they actually do carry the virus.

Unlike A. aegypti or A. albopictus, Culex mosquitoes feed (i.e., bite people) at night, and they lay their eggs in polluted standing water. Generally, the best way to avoid getting infected with a virus from a Culex mosquito is to destroy their breeding grounds by drying up standing water sources, and by taking precautions to ward off bites when outdoors at night.

The Zika Response and Preparedness Appropriations Act of 2o16 provided $350 million in funding to the CDC. The CDC announced in late-2016 that it was awarding nearly $184 million of that money in funding to states, territories, local jurisdictions, and universities. The money will be used to fund efforts to protect Americans from Zika and health implications of infection with the Zika virus.

CDC Zika Public Health Preparedness and Response Funding Table from December 2016 — a small portion of that $184 million.

The good news here is that Texas and Florida, expected to be hot spots for the virus and where cases of Zika have already been circulating, are receiving more funds out of the $25 million designated for emergency preparedness and response out of the $184 million than other states. Additionally, $8 million in supplemental funding from the $184 million has been distributed by the CDC to 38 states, territories, and local jurisdictions to develop systems to detect microcephaly.

- Follow Invisiverse on Facebook and Twitter

- Follow WonderHowTo on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Google+

Cover image via Muhammad Mahdi Karim/Wikimedia Commons

Comments

No Comments Exist

Be the first, drop a comment!