Cats give us so much—companionship, loyalty, love... and now the bird flu.

Several weeks ago, a veterinarian from the Animal Care Centers of New York City's Manhattan shelter caught H7N2 from a sick cat. According to a press release from the NYC Health Department on December 22, "The illness was mild, short-lived, and has resolved." This isn't the first time cats have passed infections on to humans, but it is the first time they passed on the bird flu—avian flu H7N2, to be exact.

Our investigation confirms that the risk to human health from H7N2 is low. We are urging New Yorkers who have adopted cats from a shelter or rescue group within the past three weeks to be alert for symptoms in their pets. We are contacting people who may have been exposed and offering testing as appropriate.

Really, it's nothing to worry about, and the H7N2 strain isn't the same flu as the frightening H5N1 bird flu strain that made its way around the globe in 2003. What's so surprising about this NYC infection is that usually these bird flu strains stay put in their avian species because their H and N proteins (that's where the H7N2 moniker comes from) are specifically adapted to live in certain species and in certain tissues.

Cats have been shown to be susceptible to infections with Influenza A, including human H2N2 and H3N2, seal H7N7, and avian H7N3. Previous to this incident, there were only two human infections with H7N2 that have been reported; Infected poultry was the source of one infection, and the other source is unknown.

In this case, it appears the cats caught the H7N2 flu from other cats, although the first cat infected may have contracted it from infected poultry. The human, however, appears to have contracted the virus from the cat directly.

The Hs & Ns of the Flu

We are used to hearing names of the flu like H1N1 or the Hong Kong flu. This year, the Centers for Disease and Prevention (CDC) says the 2016-2017 flu vaccine contains protection against H1N1 Influenza A, H3N2 Hong Kong Influenza A, and Brisbane Influenza B/Victoria. But what do all the letters and numbers mean?

There are four types of influenza viruses: A, B, C, and D. Influenza types A and B viruses cause the seasonal flu epidemics we are all familiar with. Influenza type C is not thought to cause epidemics, but it can cause a mild respiratory illness in humans. Influenza type D viruses mostly affect cattle, not people.

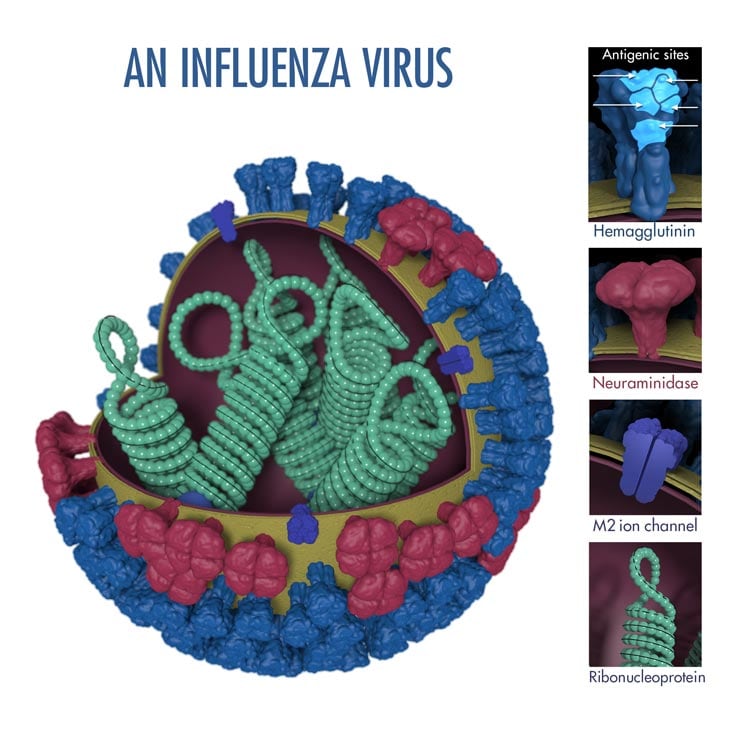

Influenza A viruses also have "H" and an "N" subtype designations that refer to two proteins on the surface of the virus. The H is a protein called hemagglutinin and the N stands for neuraminidase.

These surface proteins are necessary for the virus to infect cells. Hemagglutinin allows the virus to attach to the host cell and enter it. Once in the cell, the virus takes over, instructing it to make copies of the virus instead of going about its normal cell operations.

The neuraminidase clips the newly-made viruses from the host cell membrane when it's on its way out to infect others.

The numbers in any influenza A name refer to subtypes of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. There are 18 different hemagglutinin subtypes and 11 different neuraminidase subtypes. The subtypes of these proteins differ in their genetic code, and the amino acid sequence of their proteins. Those differences change how the proteins act and what cells and other proteins they can interact with.

The type of hemagglutinin on the virus holds the key to its infectious properties. It is also the main target of the host's immune system. This protein must be able to bind to the new host cell to be able to spread, but the ability to bind depends on the proteins on the outside of the host cell—which differ in different species and different tissues in the body.

Certain H strains are well adapted to humans, while other Hs are adapted to other animals and don't infect humans. Many H strains are adapted to live in poultry.

Hs and Ns by species.

One way the cat virus could have infected the human is if the cat was infected with a human flu virus and an avian virus at the same time. In this situation, the viruses can mix in a process called reassorting. A new virus is produced that has most of the genes from the human virus, but an H and N from the avian virus.

The cell can end up with a type of flu it has never seen before and has no immunity to. Scientists believe these new viruses probably would be able to infect humans and spread from person to person. That kind of situation is ripe for an outbreak.

Scientists believe this is what happened during some famous historical flu epidemics. They have shown that that H1, H2, and H3 from the 1918, 1957, and 1968 pandemics—world-wide epidemics—were derived from avian viruses, and the N1 and N2 of the 1918 and 1957 epidemics have also been traced back to birds.

The different types and subtypes of influenza viruses have made it possible for scientists and healthcare providers tell exactly which type is responsible for any given infection. It also helps to trace the source of infections and epidemics.

The virus that infected the cats in the NYC shelters and the veterinarian were both typed as H7N2, and allowed the NYC Health Department and CDC to link the human infection with the cats' infections.

Thankfully, H7N2 has been a weak form of the flu so far and there have been no reports of H7N2 transmission between humans.

Protecting Against H7N2 from Cats

Avian flu has been found in cats before. but cats with the flu don't infect people. Until now.

The NYC Health Department said the risk of H7N2 transmission from cats to humans is low, however, they did issue some guidelines for prevention and protection.

Here are some things you can watch for and steps you can take to help prevent catching H7N2—or any virus—from your cat:

- Wash you hands after handling your cat.

- Avoid letting your cat near your face, nose, or mouth, especially if you are pregnant or have a disease that affects the immune system, such as cancer, diabetes, or chronic lung disease.

- If your kitty is sneezing or seems to have a respiratory illness, take him or her for a visit to the veterinarian.

- Be extra alert to symptoms of a respiratory illness if you got your cat from an animal shelter.

- If you have flu symptoms, see medical care.

- The flu vaccine doesn't protect against H7N2, but getting one is a good idea anyway.

In "Influenza in Dogs and Cats," published in The Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice, Veterinarian Emily Beeler said that, "Dogs and cats may come to play a role in the evolution of new strains of human influenza."

We may just have experienced the start of that evolution.

- Follow Invisiverse on Facebook and Twitter

- Follow WonderHowTo on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Google+

Cover image by Inge Wallumrød/Pexels

Comments

No Comments Exist

Be the first, drop a comment!