As summer mosquito season approaches, researchers are warning people with previous exposure to West Nile virus to take extra precautions against Zika. A new study found that animals with antibodies to West Nile in their blood have more dangerous infections with Zika than they would normally.

Overall, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports there have been 5,238 Zika virus cases reported in the US since January 2015, and a total of 36,569 in US territories.

Already in Florida this year, two people contracted the disease locally, while 33 other cases were travel-related. In addition to applying pesticides, Florida has stepped up mosquito surveillance and education campaigns encouraging residents to drain standing water, a breeding habitat for mosquitoes that spread Zika. With above-average temperatures in the region, conditions favor the spread of the Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, the primary insect vectors of the Zika virus. Higher mosquito populations could mean a surge in Zika virus infections in coming months.

Zika and West Nile are just two of many viruses in the family Flaviviridae. This group of viruses causes more than their share of disease and death. Other well-known relatives include yellow fever and Dengue fever.

In recent years, thousands of cases of West Nile virus have sprung up across the US. Most commonly spread through the bite of an infected Culex mosquito, West Nile virus steadily encroached across the nation after it made landfall in New York City in 1999. Researchers have found West Nile in 47 US states.

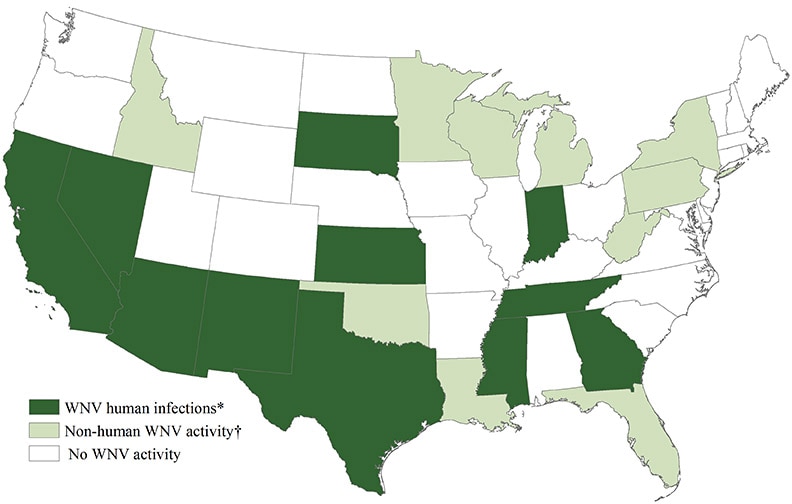

West Nile Virus Activity by State – United States, 2016 (as of January 17, 2017).

As arboviruses, Zika and West Nile are among a group of pathogens spread by arthropods, which are organisms with an exoskeleton and a segmented body. Common types of arthropods are mosquitoes, ticks, spiders, and scorpions. In the US, West Nile virus has been detected in mosquito species other than Culex, including A. aegypti and A. albopictus.

With several mosquito species that can transmit West Nile virus, the numbers of people around the country infected with West Nile virus will likely continue to rise.

In 2016, there were 2,038 reported cases of West Nile virus, with 94 deaths. While infection with West Nile virus produces mild symptoms, in 2016, 1,140 of those infected (about half of the official CDC numbers) had the more severe complications, like meningitis or encephalitis. Keep in mind, though, that these numbers are only a very small percentage of West Nile infections — many mild cases are never identified or reported. Estimates place the total number of persons infected with West Nile Virus in the US at around three million.

Once exposed to West Nile virus, a healthy immune system develops antibodies to that virus. Your immune system, once exposed to a virus, will then recognize and shut down the virus in the future before it causes a full-blown infection.

A recent study published in Science suggests that prior infection with a flavivirus, like West Nile or Dengue, could result in more severe disease — and complications — in the case of a future infection by Zika virus.

Map showing states with confirmed cases of Zika (travel-related and local).

In the study, scientists investigated the concept of antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) as it applies to flaviviruses like Zika, West Nile, and Dengue. ADE is a complicated immune response, but basically, it goes like this:

- When infected, the body creates antibodies and T cells specific to an invading pathogen, which helps the immune system target and take out the invading organism.

- Successfully fighting off a virus usually leads to immunity against that specific infection, because the immune system recognizes the virus, and having already created antibodies, can shut down infection.

- With ADE, infection with Zika, after an infection with Dengue or West Nile, could cause more severe Zika complications because of related flavivirus antibodies in the blood. Antibodies created in response to the first flavivirus infection cause ADE because they somehow make it easier for the next flavivirus to invade body cells, and making the infection, and its symptoms, worse.

In this study, researchers found that 146 mice injected with human antibodies to flaviviruses like West Nile and Dengue suffered more complications when later infected with Zika. After receiving Dengue antibodies, only 21% of Zika-infected mice survived, while more than 90% of mice given no antibodies survived the Zika infection. Survival of mice with West Nile antibodies also decreased when later infected with Zika.

Scientists suggest this could partially explain why congenital disabilities like microcephaly and other complications from Zika were higher in areas of Brazil where Dengue fever is common. Study authors report:

Our results suggest that preexisting immunity to Dengue virus may have contributed to the rapid spread of Zika virus in the Americas, possibly associated with increased viremia and clinical symptoms, including microcephaly.

Researchers point out "the high prevalence of West Nile virus antibodies in the US raises concerns if Zika virus continues to spread into North America." In a press release, study author and microbiologist at Mount Sinai Jean Lim expanded on that worry, commenting, "The findings may also have implications for people who develop Zika in the United States, where more than have been infected with West Nile virus."

Also of concern are experimental Zika vaccines in development that may cause enhanced symptoms if given to individuals already exposed to Dengue or West Nile fever. One way to prevent this reaction would be to create a combination vaccination that prevents Zika, Dengue, or West Nile fever at the same time, thereby avoiding later infection by these flaviviruses. There is already a vaccine for yellow fever, a potentially deadly flavivirus also spread by mosquitoes.

In the meantime, prevention of mosquito-borne pathogens is important. Use effective DEET mosquito repellent, wear long sleeves and pants, stay clear of mosquito habitat at dawn and dusk, and stay tuned.

- Follow Invisiverse on Facebook and Twitter

- Follow WonderHowTo on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Google+

Cover image via Brubakerslegacy/Wikimedia Commons

Comments

No Comments Exist

Be the first, drop a comment!