The number of households in the US that go hungry because they lack money for food hit a high of almost 15% in 2011. While that number continues to decline, nearly 13% of American households still go hungry.

Malnutrition — either from not eating enough or not getting enough nutritious food — causes changes in the gut bacteria. A new research study has found how two gut bacteria commonly found in malnourished children can worsen malnutrition and inhibit growth in laboratory mice.

The two bacteria are pathogens — disease causing microbes — and when they infected protein-deficient mice, the researchers found changes in their immune responses to the infections. To study how the bacteria and malnutrition worked together to bring about these changes, they modeled the same conditions in mice.

Study researcher Luther A. Bartelt, from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, published the research July 27 in PLOS Pathogens.

The Bacteria-Malnutrition Cycle

Bartelt and his team developed a way to study the effects of infection and malnutrition by creating a model in mice. To do that, they fed mice a protein-deficient diet and infected them with Giardia lamblia, a parasite, then two weeks later, with a pathogenic E. coli. Both are organisms commonly found in malnourished children.

Next, they examined mice stool, cells, and urine using different types of tests. They used flow cytometry to identify different types of immune cells; 16S rRNA analyses to categorize the bacteria present; light microscope studies to see changes to tissue and presence of parasites in the gut; and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to measure metabolic products in the mice urine to evaluate how the gut was functioning.

Stained tissue of gut in infected mice fed protein-deficient diet. Arrows show immature parasite.

Malnourished mice infected with E. coli experienced a rapid loss of 7% of their body weight in three days. The weight loss correlated with impaired metabolism —

shown as abnormal urine metabolites — and changes in the mucosal lining of the intestines leading to malfunctions in the immune system.

Bacteria in the gut of mice infected with both Giardia and E. coli broke down even more of the body's protein, contributing to the already-established malnutrition. The two pathogens doubled the weight loss in malnourished mice. When the researchers fed mice infected with both pathogens a regular diet, the mice did not lose weight — which suggested to the researchers that the malnutrition worked with the pathogens to cause changes that resulted in weight loss.

Giardia infection increased signals from the immune system released in response to intestinal injury by the parasite, but decreased proteins associated with inflammation when E. coli was also present. Specifically, fecal myeloperoxidase — an enzyme produced by white blood cell neutrophils that make bacteria-killing acids — was elevated in protein-deficient mice in response to either pathogen alone, but decreased to levels similar to uninfected controls in co-infected mice. This led the scientists to believe that damage to the mucosal intestinal lining by Giardia inappropriately decreased the immune response to E. coli that otherwise might have cleared the infection.

The study authors said that the inappropriate suppression of inflammatory proteins that occurred during malnutrition and co-infection might serve as an alarm that host immune and metabolic functions are perturbed and will result in worsening disease, including additional weight loss. Measurement of these immune signals and fecal myeloperoxidase might give clues to gut disease in malnourished humans, especially children, that can affect their growth and health.

The mouse model proved useful in studies of co-infection in a protein-deficient host and can help with other long-term studies of malnutrition in children. Eventually, the studies may contribute to improving existing treatments or developing new ones that can restore healthy guts in malnourished children and address the contribution of malnutrition itself to related health issues like this in children.

- Follow Invisiverse on Facebook and Twitter

- Follow WonderHowTo on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Google+

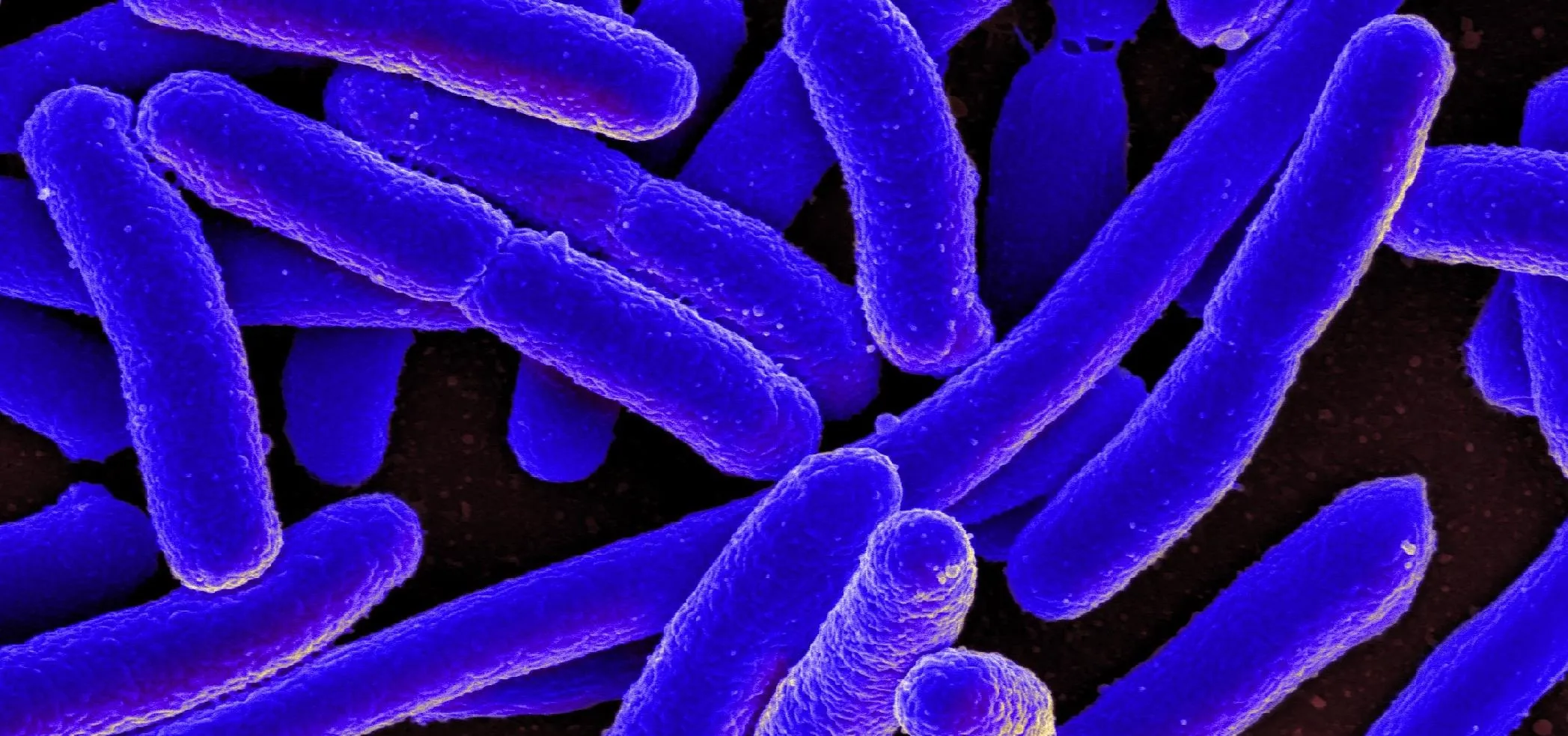

Cover image via NIAID/Flickr

Comments

No Comments Exist

Be the first, drop a comment!