The growing list of dangerous antibiotic resistant organisms has just acquired three new members. Researchers have discovered three new species of Klebsiella bacteria, all of which can cause life-threatening infections and have genes that make them resistant to commonly used antibiotics.

Bacteria that have become resistant to antibiotics are causing infections in hospital patients, people with other serious illnesses, and even people in the community. Unless we can figure out new ways to treat these infections, an estimated ten million people a year are expected to die of antibiotic-resistant infections by 2050.

The research study, by S. Wesley Long of Houston Methodist Hospital in Texas, and colleagues, was published August 2 in the journal mSphere.

The Growing Threat of Antibiotic Resistance

Hospitals should be somewhere we go to get better, but there were over 700,000 healthcare-associated infections — pneumonia, sepsis, wound infections, and urinary tract infections — in the US in 2011. One bacteria, Klebsiella pneumoniae is particularly virulent. Up to 50% of invasive, multi-drug-resistant infections with the bacteria are fatal.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has named carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae to its highest level of global healthcare threats — an urgent threat. CDC ranked organisms based on clinical impact, economic impact, incidence, the 10-year projection of incidence, transmissibility, availability of effective antibiotics, and barriers to prevention. Infection with microbes in the urgent threat category has a high mortality rate and high potential to cause widespread infection due to lack of effective treatment. Klebsiella species are Enterobacteriaceae. Of the 9000 carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections per year, 7900 are caused by Klebsiella. Klebsiella shares the top billing of "urgent" with Clostridium difficile and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is in the next lower category, serious threats.

The cause of rising antibiotic-resistant organisms is complicated. Increased use of antibiotics has created an almost-constant exposure, especially in healthcare facilities, that favors bacteria that have mutated to survive the antibiotic treatment. Inappropriate use of antibiotics as prophylaxis and for use to treat viruses — which they don't — or prescribing without knowing if the drug is suitable for a particular infection, all promote the development and survival of antibiotic-resistant organisms. Another source of exposure to antibiotics is through the food we eat. Animals treated with antibiotics allow antibiotic-resistant bacteria to thrive in the animals where they are transmitted to humans through the food supply.

According to the World Health Organization:

While more R&D is vital, alone, it cannot solve the problem. To address resistance, there must also be better prevention of infections and appropriate use of existing antibiotics in humans and animals, as well as rational use of any new antibiotics that are developed in future.

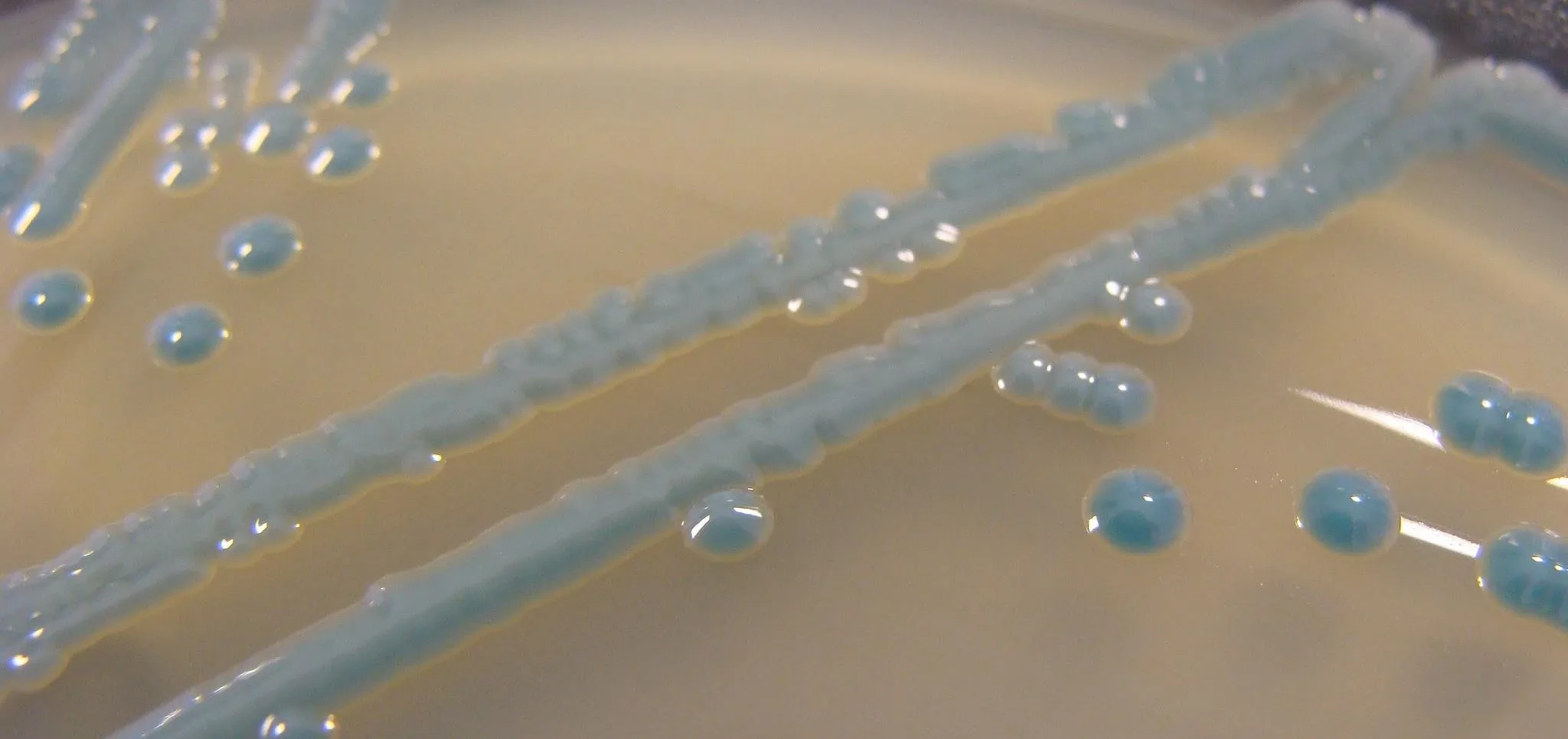

Klebsiella pneumoniae was thought to cause the most severe Klebsiella infections, but the team's new research blew that assumption wide open.

Meet the New Klebsiellas

The research team had already sequenced the entire genome of 1777 Klebsiella from patient samples.

"We built a genetic family tree, essentially, and 28 strains stick off the tree as outliers. These are cousins five times removed, and we wondered what are these guys doing at the family reunion?" said Long in a press release from the American Society for Microbiology.

The 28 distant cousins became the subject of the team's new research study. Their study revealed that between 2–12% of the samples had been misidentified as Klebsiella pneumoniae, and were actually two related species, Klebsiella variicola or Klebsiella quasipneumoniae. Those two bacteria were thought to live in the human gut without causing infection. Instead Long and his team found both Klebsiella variicola or Klebsiella quasipneumoniae were capable of causing severe infections in patients who were the source of the bacterial sample, with a resulting death rate similar to that of Klebsiella pneumoniae.

"Not only are these cousins of K. pneumoniae causing similar infections, but they are also sharing these powerful drug resistance genes," said Long.

Besides revealing the genetic relationship of the bacteria, sequencing of the bacteria showed that all three Klebsiella species shared antibiotic-resistance genes, including at least two genes that code for resistance to carbapenemase capable of disabling a broad spectrum of penicillin-like antibiotics. One Klebsiella variicola strain was found carrying another antibiotic gene, New Delhi Metallo-beta-lactamase-1, that confers resistance to penicillin, cephalosporins, carbapenems, and monobactams — all antibiotics used to kill a wide variety of bacteria.

Genetic sequencing also found that the different Klebsiella species all contained bits of bacterial DNA called plasmids that contained antibiotic resistance genes. Plasmids are double-stranded DNA that is separate and distinct from a cell's chromosomal DNA. They naturally exist in bacterial cells and can transfer genes (including those for antibiotic resistance) between the bacteria. Plasmids are passed to daughter cells when a bacteria divides, and they can move from one bacteria to another through close contact called conjugation.

Because the different Klebsiella species so closely resemble each other, standard laboratory techniques may not be able to tell them apart, increasing the potential for inadequate treatment and further spread of these life-threatening bacteria.

The closer look at these distant cousins has identified genetic traits that might be targets of new investigations into their treatment and antibiotic resistance — the urgent threat to global health.

- Follow Invisiverse on Facebook and Twitter

- Follow WonderHowTo on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Google+

Cover image by Nathan Reading/Flickr

Comments

No Comments Exist

Be the first, drop a comment!